Super 8 Filmmaking in Paris: Geographies of Identity

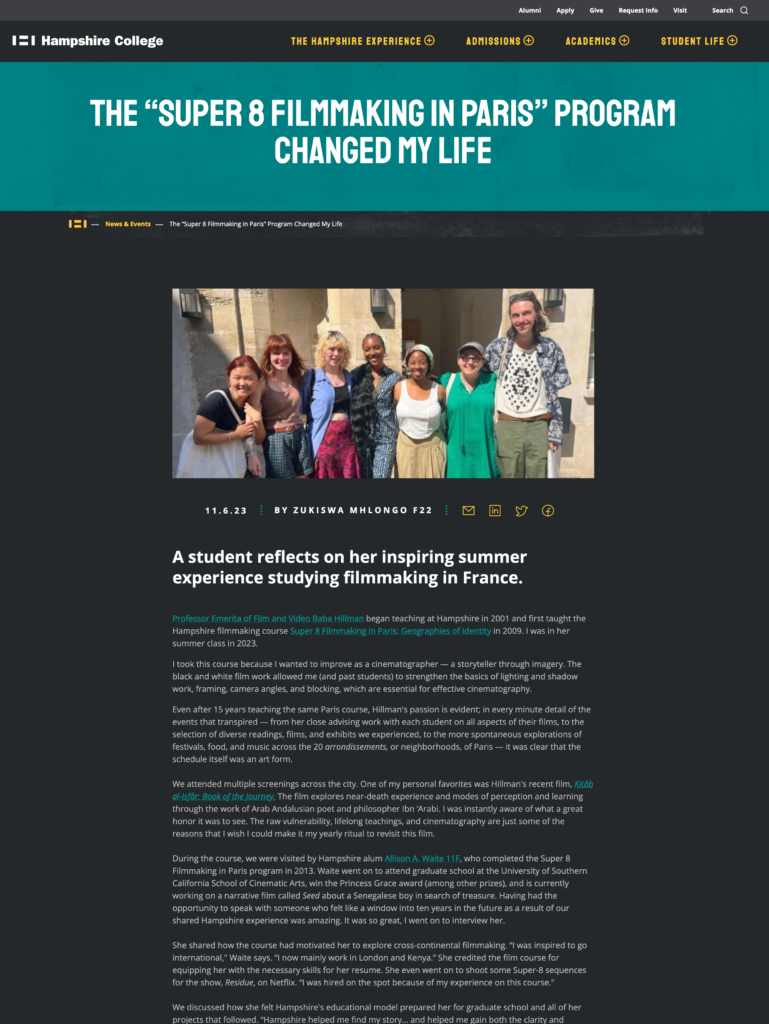

This course combines intensive workshops in Super 8 filmmaking and film theory. The class includes workshops on cinematography, hand-processing, animation and editing on Super 8 film. Each student will shoot, process, edit and complete a short Super 8 film. All cameras, film and editing equipment are provided. The course has included studio visits with filmmakers, artists and writers including Nicole Brenez, Johanna Vaude, Mike Ladd, and Zoulikha Bouabdellah among others.

Film workshops are taught by Baba Hillman and by members of French filmmakers’ cooperatives. Students are asked to write detailed proposals for their films, with a bibliography of related films and readings. We have access to the film library of the Forum des Images, which has the largest collection of films shot in the city of Paris and the surrounding suburbs.

Students attend screenings, performances and exhibits at the Cinématheque Française, Palais de Tokyo, Centre Pompidou, L’Institut du Monde Arabe, Le Champo, Le Centquatre and other cinemas, galleries and museums throughout the city. Critical work concentrates on the role of migration and diasporic communities in contemporary transnational film in Paris through a study of language, performance and visual structure within selected films. Seminars address such topics as changing cinematic representations of the architecture and urban space of the city, and the politics of film funding, production and distribution in France.

Prerequisites: Introductory film, video, studio art, performance course or other media practice/theory course. Course events are presented in both French and English. There are no language prerequisites.

Visiting Artists & Curators

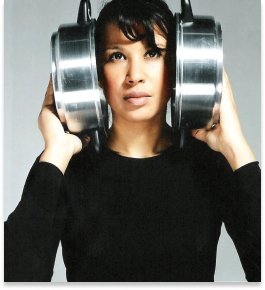

Zoulikha Bouabdellah was born in Moscow, Russia, in 1977. She grew up in Algiers and moved to France in 1993. A graduate of the Ecole Nationale Superieure d’Arts de Cergy-Pontoise in 2002. Zoulikha Bouabdellah’s works, in installation, drawing, video and photography, deal with the effects of globalization and question their depictions with humour and subversion.

In 2003, she directed the video Let’s Dance (Dansons) in which she confuses the archetypes of French and Algerian cultures by performing a belly dance to the tune of the Marseillaise. The same year, her work featured in Experiments in the Arab Avant-garde at the French Cinémathèque (Paris). In 2005, Zoulikha Bouabdellah participated in Africa Remix at Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris), and in 2008 in the festival Paradise Now! Essential Avant-Garde French Cinema 1890-2008 at the Tate Modern (London). Since 2007, Bouabdellah’s works focus on letters and words of love, and particularly on the status of women. Made with different materials – paper, acrylic, aluminum, neon, wood – her works act as slogans and forge links between North and South, joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain, the visible and unsaid. She has exhibited at the Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), the Brooklyn Museum (New York), Museum of Modern Art Ludwig Foundation (Vienna), the Museum Kunst Palast (Düsseldorf ), the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (New York), the Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art (Doha) and the Moderna Museet (Stockholm). She has participated in several biennials and festivals including the Venice Biennale (2007), Rencontres de la Photographie Africaine in Bamako (2003), Thessaloniki Biennial (2011).

Artiste et réalisatrice, Johanna Vaude crée des films éclectiques. Son parcours révèle différentes périodes, partant d’un savoir-faire en arts et cinéma expérimental (peinture sur pellicule, footage, stock-shot, flicker, animation image par image) qu’elle étend jusqu’aux nouvelles technologies (mashup, recut, motion design, modélisation 3D…). La combinaison et la relation des images classiques et expérimentales engendrent des films inclassables qui oscillent entre avant-garde, clip, pop art, poésie introspective, expériences sensorielles, psychédélisme, rêve et fiction.

Son cinéma hybride, basé sur une relation entre les images et le son, aborde des thèmes très étendus en privilégiant le point de vue intérieur de ses sujets et en créant des univers intenses aux couleurs et aux montages insoupçonnés.Ses premiers films acquièrent une reconnaissance critique (Libération, magazine Bref, Encyclopédie du court-métrage, Cahiers du cinema Espana… ) et dépassent les frontières établies. Ils sont projetés dans des institutions (Frankfurt Film Museum, Tate Modern, Jeu de paume, Beaubourg) sélectionnés dans des festivals de court-métrage et des focus leur sont consacrés alors qu’ils ont été confectionnés hors des systèmes traditionnels (MK2 Beaubourg, Cinémathèque Française, Festival Côté Court de Pantin, Pesaro Film Festival, News form festival, LUX National de Valence,…).

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Mike Ladd is influenced by Funkadelic, Charles Stepney, Bad Brains, Burt Bacharach, Kraftwerk, Bollywood, Jungle Brothers and Divine Styler.

Mike Ladd has released several solo albums, including Easy Listening 4 Armageddon, Welcome To The Afterfuture, Negrophilia, Father Divine and Nostalgialator. He also released Gun Hill Road and Bedford Park as The Infesticons and Beauty Party as The Majesticons. He released two collaborative albums, In What Language? and Still Life With Commentator, with jazz pianist Vijay Iyer. He has collaborated with artists such as Company Flow, Rob Sonic, Saul Williams, U-God, Busdriver, Blue Sky Black Death, Daedelus, Jackson and his Computer Band, Coldcut, DJ Spooky among others. He has remixed songs for the likes of Yo La Tengo, Antipop Consortium and Enrico Macias. Mike Ladd has toured extensively for several years throughout America, Europe and Asia, establishing a cult following in the process.

Mike Ladd received his B.A. in Black expatriates in the Nineteenth century from Hampshire College and an M.A. in Poetry from Boston University. As a Fellow at the Institute for Arts and Civic Dialogue at Harvard University, he produced and directed Blood Black and Blue, an audio documentary/performance about Black police officers in the United States. In 2005, he completed a fellowship at the Asia Society, where he created a musical/theatrical/visual installation In What Language? with Vijay Iyer. It was a project about people of color in relation to globalization in the context of airports. They also put up another installation Still Life with Commentator, which was commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music for 5 nights of performances.

Mike Ladd has been published in several literary magazines including Long Shot Review and Bostonia. His work is also featured in the book Swing Low, Black Men Writing and several anthologies, including, Aloud: Voices From The Nuyorican Poets Café, In Defense Of Mumia, Bum Rush The Page, Por La Victoire and Everything But The Burden.

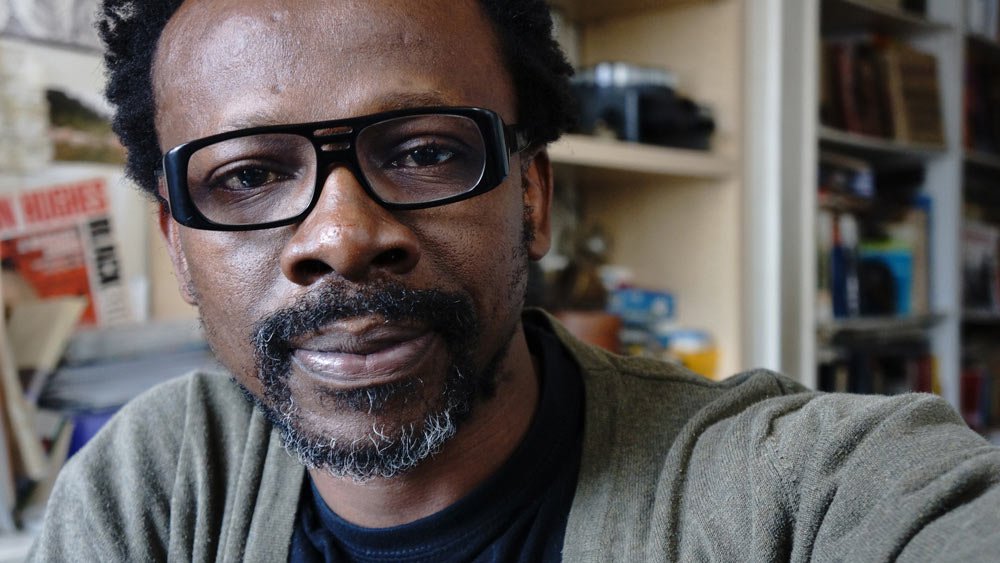

Né en 1966 à Ogidi, à l’Est du Nigéria. À la fin de la guerre du Biafra, en 1970, sa famille s’installe à Lagos. En 1985, il part pour l’Angleterre afin d’effectuer des études d’ingénieur mais il découvre le cinéma et est admis à la London International Film School, d’où il sort diplômé en 1990.

En 1997, il fonde Granite Filmworks, la branche britannique de Granit Films. La même année, il écrit, produit et réalise son court-métrage lauréat, On The Edge, suivi de son premier long-métrage, Rage. En 2001, Rage est le premier film totalement indépendant de l’Histoire du cinéma britannique réalisé par un cinéaste noir à être distribué sur l’étendue du territoire national, et sort avec un fort succès critique. La même année, Newton Aduaka est sélectionné comme résident de la Cinéfondation du Festival de Cannes et part s’installer à Paris. En 2004 et 2010, Global Dialogue, commande à Aduaka quatre courts-métrages de prévention contre le SIDA. Ces films sont traduits dans de nombreuses langues et utilisés comme outils pédagogiques à travers le monde.

Avec Ezra, en 2007, Newton I Aduaka remporte l’Étalon d’or de Yennenga au Fespaco, la plus grande récompense pour un cinéaste africain. La première d’Ezra se déroule sous les auspices de la section internationale du festival de Sundance. Le film est également nominé pour le Prix Humanitas et projeté en séance spéciale à la Semaine de la Critique du Festival de Cannes. Ezra a été sélectionné dans plus de cent festivals à travers le monde et a remporté plus de 20 prix, parmi lesquels 6 grands prix et celui de la Fipresci. Ezra a été cité comme l’un des films pacifistes les plus importants jamais réalisés et a reçu le Prix de la paix et de la tolérance des Nations-Unies.

nicole-brenez

Nicole Brenez teaches film studies at Paris 3 University and curates the experimental and avant-garde programs at the Cinémathèque Française. Author of several books, with Philippe Grandrieux she produced the collection It May Be That Beauty Has Strengthened Our Resolve, devoted to revolutionary filmmakers.

Silke Schmickl studied Art History, French Literature and Intercultural Communications in Munich and in Paris where she completed her master’s degree at the Sorbonne University in 2001. She has been a researcher at the German Center for Art History in Paris where she has published a book on the German photographer Thomas Struth. In 2002 she co-founded the Paris based DVD label Lowave, specialising in releasing and distributing experimental film and video art, which she directs since 2007. Within this structure she is in charge of the conception and realisation of artistic projects and curates film programs for international art institutions and festivals such as the Pompidou Centre, French Cinémathèque, British Film Institute, Museet for Samtidskunst Roskilde, Guangzhou Triennial and many more.

Student Writings

Click to read what Hampshire students had to say about the course